Most organisations lose good people for predictable reasons. They leave not because they have lost interest, but because their work has become stagnant. While everything else moved on, the structure around them stayed still.

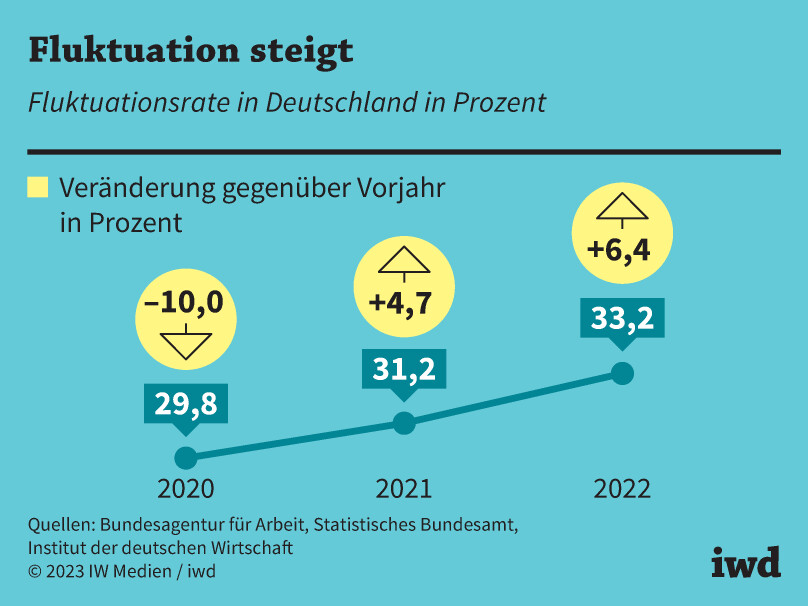

Across Germany, turnover is rising again. According to Haufe, the average rate is between 30 and 34 per cent across industries. Many of these departures occur in the early stages of employment. According to the Institute of the German Economy (IW Köln), one in two employment relationships ends within the first year. Short tenures are becoming the norm, particularly among younger professionals. This is not just a recruitment issue. It is a sign that there is a deeper issue with the way work is structured.

The true cost of staff turnover

The direct costs of someone resigning are easy to calculate. The cost of replacing a mid-level employee can quickly reach five figures, once you add up the separation, hiring and onboarding costs. Haufe categorises these costs into three stages: the exit itself, the recruitment process, and the period of time it takes for a replacement to reach full capacity. However, the indirect costs are often higher. Teams lose continuity, clients notice gaps and projects slow down as knowledge must be rebuilt.

Frequent staff turnover quietly drains organisational energy. It sends a message to those who stay: commitment has an expiry date. Even highly motivated teams become cautious. They hesitate to invest emotionally when they have seen too many colleagues leave. Over time, staff turnover becomes less about individuals and more about system fatigue.

Motivation is not enough.

The IW’s 2025 study on work motivation reveals a lot. Almost half of employees in Germany describe their job satisfaction as high, while a further 49 per cent describe it as moderate. 90% believe they do good work. On paper, this sounds positive. Yet average tenure continues to fall, especially among younger age groups. On average, employees under 30 stay with the same employer for just three years.

The study shows that a lack of motivation is not the problem. People want to contribute, learn, and perform well. What they lack is a long-term structure that enables them to do so. When career paths are too narrow or advancement depends solely on hierarchy, motivation can turn into impatience. People do not quit because they dislike their job. They quit because they see no opportunity for growth within it.

Rigid job architectures create silent turnover.

A company’s job architecture the connections between roles, levels and pay structures. Its purpose is to provide clarity and fairness. However, when it becomes static, the opposite effect is achieved.

Rigid architectures assume that roles are stable. They rarely are. Projects expand, technology shifts and skills evolve faster than HR frameworks can keep up with. Job descriptions that were accurate two years ago now seem outdated. Employees notice the mismatch long before management does.

This is how silent turnover begins. People mentally check out long before they leave. They either take on new tasks without recognition or downshift into ‘working to rule’, doing only what is required. The organisation loses engagement long before it loses staff.

A living job architecture.

A modern job architecture is not just a spreadsheet. Rather, it is a living system that adapts as the business and its employees evolve.

It strikes a balance between structure and freedom. It provides clarity without stifling progress.

The following five principles define a living job architecture:

- Design around capabilities, not job titles.

Titles are convenient, but they reveal little about what someone can actually do. Designing around core capabilities makes it easier to recognise transferable skills and redeploy people when priorities change. This also enables HR to link learning and performance data to genuine organisational requirements. - Use levels to describe scope, not hierarchy.

A healthy organisational structure distinguishes between expertise and management. Not everyone should have to become a manager to progress. Having dual career paths — one for leadership and one for professional mastery — reduces frustration and broadens growth opportunities. - Make internal mobility a real option.

In many organisations, the easiest way to change roles is to change employers. This is a structural failure. Cross-functional moves, project-based assignments and lateral shifts are the solution. These options keep learning alive and reduce early exits. - Keep job definitions current.

Review and update role descriptions regularly. They should reflect reality, not history. A short quarterly check by managers and HR can prevent the discrepancy between theory and practice that causes disengagement. - Integrate skills, data and dialogue.

Technology can help, but culture completes the process. Modern tools can track evolving skills and match them to roles. However, the real impact is achieved when these insights inform honest conversations about growth. People will stay if they can see their future in the organisation’s data and their manager’s plans.

The labour market context

According to the German Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs (BMAS), the labour supply in Germany has peaked. Fewer workers are entering the labour market, while demographic shifts are accelerating retirements. Meanwhile, the Fachkräftemonitoring report highlights an increasing mismatch between qualifications and job requirements. While many professionals are underemployed relative to their skills, other positions remain chronically unfilled.

This shortage alters the logic of retention. In a shrinking labour market, each departure is more damaging. Not only is recruiting replacements expensive, it is also often impossible within a reasonable timeframe. Organisations that build flexible systems to retain their existing employees and make better use of their skills will thrive.

The Economics of Flexibility

Rigid structures used to offer a sense of security. Today, however, they create friction. A company that locks roles too tightly makes adaptation costly and staff turnover inevitable. By contrast, flexibility lowers costs over time.

When job architectures are designed to be flexible, HR gains a powerful advantage. Skill data can reveal where new competencies are emerging and where existing talent can be redeployed internally instead of leaving. A transparent structure makes career growth visible, building trust. It also supports fair pay decisions, since roles are defined by scope and contribution rather than titles or negotiation strength.

In this sense, job architecture is not just an HR tool. It is an economic strategy. Reducing staff turnover not only saves direct costs, but also preserves experience, culture and continuity — the invisible assets that make organisations resilient.

Building Retention Through Structure

Retention is often considered an emotional outcome. We assume that people stay because they feel appreciated. While this is partly true, appreciation alone cannot offset a broken system. Structure shapes experience more than slogans do.

A flexible job architecture sends a clear message that growth is possible here. It shows employees that their work evolves alongside them, that their skills are recognised, and that there are multiple career paths. It turns career planning into a shared responsibility between HR, managers, and individuals.

Companies that master this will not only reduce staff turnover, but also attract people who value clarity and autonomy. They will become places where development feels natural rather than bureaucratic.

A Different Kind of Stability

The old logic of stability focused on maintaining constant roles and hierarchies. The new logic, however, is about maintaining continuous growth. Flexibility does not mean chaos; it means responsiveness.

By regularly reviewing job structures, integrating skills into workforce planning, and encouraging lateral movement, HR teams can foster stability through change. People do not leave because things change. They leave because things don’t change.

A well-designed job architecture creates order without rigidity. It connects purpose with potential. It gives people a reason to stay — not because they have to, but because it makes sense.

Conclusion

Turnover is not just an HR metric. It is a key indicator of organisational health. When roles stop evolving, people move on. When structures adapt, people stay.

Reducing turnover starts with redefining what work itself is. A modern job architecture does not restrict people’s potential. It provides pathways for growth.

The aim is not to retain everyone at all costs, but to create an environment in which the best people choose to stay because they can develop professionally.